Jump To:

- Latest

- Explanation and Scientific Epistemology

- Causal Reasoning in Biology

- The Methodology of Integrated History and Philosophy of Science

- The History of Philosophy of Science

- Miscellaneous

- Biomedical Research

Latest 🔝

John Stuart Mill: Wissenschaftstheoretischer Diskurs

This German-language contribution considers the recent reception of John Stuart Mill’s philosophy of science. While Mill continues to be seen as a relevant participant in debates in moral and political philosophy, there is a tendency to belittle Mill’s philosophy of science. The methods he articulated are considered to be not only simplistic and unsound, but also far removed from actual scientific practice. I argue that these are misjudgments. In the light of historical and philosophical scholarship of the past decades, many aspects of Mill’s philosophy of science come out looking more relevant than ever. With his canons of experimental inquiry, Mill gave a clear (although imperfect) outline of causal reasoning strategies that can be found throughout the history of science. They do much of the day-to-day work of scientific inquiry, their development is a key aspect of the history of scientific methods, and they avoid significant conceptual difficulties that plague competing approaches. Mill’s methods are also extremely well aligned with the renewed interest in causality, mechanisms, and comparative experimentation among historians and philosophers of science. Finally, we can learn from Mill’s view that understanding scientific methods is not an a priori project.

The contribution is an open homage to Philip Kitcher’s entry in the Cambridge Companion to Mill, in which Kitcher argues that Mill’s much-ridiculed philosophy of mathematics is one of the most promising approaches on offer.

Scholl. R. (forthcoming). “Wissenschaftstheoretischer Diskurs“, in F. Höntzsch, ed., Mill-Handbuch: Leben, Werk, Wirkung. J.B. Metzler, pp. 361–378.

Explanation and Scientific Epistemology 🔝

Inference to the Best Explanation (IBE) is a leading account of inductive inference. Not only philosophers of science but also philosophically inclined scientists often presuppose that (some version of) IBE is how hypotheses are confirmed or disconfirmed by evidence — that is, that we accept hypotheses that would best explain the evidence if they were true. IBE appeals to our intuitions: Our best scientific theories explain lots of things, and so it is tempting to suspect that we have come to accept them because of their explanatory power.

But evidence from detailed case studies from the history of the life sciences does not back up the IBE account. While potential explanatory power may be a reason to pursue a hypothesis, it is not the basis on which hypotheses are accepted. To the contrary, hypotheses that are supported only by their explanatory power are viewed with skepticism. Instead, hypotheses are typically tested using causal reasoning strategies that do not rely on an assessment of explanatory power.

I argue that recognizing this has important implications for central issues in scientific epistemology. In particular, it throws new light on the stability and instability of our scientific beliefs, that is, on issues surrounding medium- and long-term theory change and scientific realism. While my case studies are generally from the life sciences, many of the core findings may well apply in other disciplines.

Causal inference, mechanisms, and the Semmelweis case

Ignaz Semmelweis’s discovery of the cause of childbed fever in mid-19th-century Vienna has a long history as a case study in philosophy of science. Philosophers have returned to it again and again as a “simple illustration” (to quote Carl Hempel) of scientific discovery and justification. To mention just the two most prominent examples, Hempel used the case as an illustration of the hypothetico-deductive method of hypothesis testing, and Peter Lipton used it as a case study of inference to the best explanation — arguing that Hempel’s account was both too permissive (in that it in principle licensed many more inferences than Semmelweis actually made) and too restrictive (in that it could not justify some inferences that Semmelweis actually did make).

In this paper, I show that Semmelweis’s inquiry should be understood in terms of causal reasoning strategies. Semmelweis deployed many of the methods for causal reasoning that contemporary authors (most prominently John Stuart Mill) described as the central inferential machinery of science. In addition to the method of difference, we also find the methods of agreement, concomitant variation, and residues. Part of the reason why this aspect of Semmelweis’s reasoning has been overlooked is that much of the story is not in Semmelweis’s text, but in his many numerical tables. It is telling that these tables were often abridged by editors of Semmelweis’s main work, The Etiology, the Concept, and the Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever (1861). Their significance was clearly not appreciated. Furthermore, I show that on the causal reasoning account, Semmelweis’s animal experiments — which appear superfluous or at least supererogatory on the HD and IBE accounts — must be seen as a central part of the inquiry. Again tellingly, these experiments have also been abridged in the most prominent English-language edition of Semmelweis’s Etiology.

Scholl, R. 2013. Causal Inference, Mechanisms, and the Semmelweis Case. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 44(1): 66–76. [PhilSci Archive version.]

Inference to the best explanation in the catch-22: How much autonomy for Mill’s method of difference?

The previous paper argued for the descriptive adequacy of a causal reasoning account of Semmelweis’s work. However, this leaves open the question of whether these causal reasoning strategies can justify Semmelweis’s inferences. One of the argument strategies in Lipton’s Inference to the Best Explanation was to grant that aspects of Semmelweis’s reasoning could well be described in terms of Mill’s method of difference. When Semmelweis instituted hand hygiene measures to show that removing residues of “cadaverous matter” from the hands of physicians led to a decrease in the incidence of childbed fever, a reconstruction in terms of the method of difference is obvious. However, Lipton argued that the method of difference could not actually justify Semmelweis’s inferences unless it was embedded in the IBE framework.

Lipton argued that Mill’s method of difference encounters two problems. The first is the “problem of multiple differences”: Can we be sure that the control and the intervention in our experiment differ only in the presence or absence of our intervention? If other variables change in the background, then our inference to causal relevance becomes uncertain. The second is the problem of inferred differences: Often we experiment to infer the causal role of entities that are not directly observable (such as Semmelweis’s cadaverous matter residues), so that the very existence of the suspected cause is itself inferred. If inferences using Mill’s method of difference are to be justified, Lipton concluded, we need an explanationist framework to solve these two problems.

I argue that both problems can be dissolved by careful attention to Semmelweis’s actual inferential procedures. Semmelweis did not need to rely on explanatory considerations to decide that cadaverous matter was really the relevant difference between the control and the intervention in his experiment. Instead, he based his judgment on the logic of the control experiment, which he deployed in sophisticated ways. Nor did Semmelweis have to infer the existence of invisible cadaverous matter residues on explanatory grounds. His primary method for determining that residues remained on the hands of physicians even after all visible traces of cadaverous matter had been removed was to detect those residues — by using the humble sense of smell.

Overall, the Semmelweis case study forcefully demonstrates why inference to the best explanation is so appealing to philosophers of science. It can be used to justify inferential steps that seem puzzling to those without a deep knowledge of the relevant science and scientific practice. At the same time, the case study also shows how the IBE accounts tend to dissolve as soon as we carefully study the relevant historical sources. The way that the inferences are actually accomplished is both more ingenious and also more pedestrian than the IBE account imagines.

Scholl, R. 2015. Inference to the Best Explanation in the Catch-22: How much autonomy for Mill’s method of difference? European Journal for Philosophy of Science 5(1):89–110. [PhilSci Archive version.]

Presume It Not: True Causes in the Search for the Basis of Heredity (with Rose Novick)

One of the strongest cases for anti-realism about science is Kyle Stanford’s “problem of unconceived alternatives”. Stanford offers us both a) a mechanism to explain why the history of science is marked by very powerful theories that nevertheless fail in the medium to long run, and b) a demonstration that the mechanism has actually operated in the history of science. The mechanism is that scientists rank candidate hypotheses by their explanatory power, but even if we grant that they can do this reliably — and that explanatory power is a mark of truth — it may still turn out that an even better theory existed but was not among the candidates being ranked. This explains why we often end up with very powerful explanations (our theories were the best of the lot) that nevertheless turn out to be mistaken (the lot from which we made our selection was limited). In addition, Stanford demonstrated that this mechanism has operated in nineteenth-century theorizing about heredity. He showed that theorists such as Darwin, Spencer, and Weismann committed to and vehemently defended theories that offered powerful explanations of the phenomena of development and heredity. However, their theories were soon rejected because all of them had chosen the best explanation from a limited set of candidates, falsely believing no plausible additional alternatives to exist.

Here we show that the threat of unconceived alternatives is more limited than Stanford’s account suggests. Although Darwin may have committed to his “provisional hypothesis of pangenesis” because of its explanatory power, the rest of the scientific community granted the explanatory power but did not regard this as a reason to adopt the theory. Critics with all kinds of backgrounds — physicalists and vitalists alike — pointed out that the hypothesis could not be accepted precisely because alternative hypotheses with equal or superior explanatory power might well exist. So the scientific community as a whole was well aware of the dangers of inferring to the best explanation in non-exhaustive hypothesis spaces. The community demanded a different sort of evidence in line with the classical “vera causa” norm. According to this methodological norm, a legitimate scientific explanation requires that we provide evidence, first, for existence of a postulated cause; second, for its competence to produce the phenomena ascribed to it; and third, for its responsibility for the phenomenon in specific instances. Importantly, existence and competence cannot be demonstrated by a speculative cause’s explanatory power alone. What is required is direct evidence for existence in the form of appropriate methods for observation or detection, and direct evidence for competence in the form of comparative experiments or other appropriate strategies. Darwin tried but failed to provide such evidence for his hypothesis of pangenesis.

By extending Stanford’s case study into the twentieth century, we show that the still-accepted milestones of genetics all met the requirements of the vera causa norm and were accepted for this reason. The scientists who demonstrated that genes are linked to chromosomes (T.H. Morgan’s group) and that (some) genes consist of deoxyribonucleic acids (Oswald T. Avery and collaborators) rejected explanatory power as a justification for accepting hypoteses, and instead required direct evidence for existence and competence. These preferences reveal themselves both explicitly in the scientists’ methodological writings and implicitly in their actions. We argue that given the more demanding evidential requirements of the vera causa norm, the problem of unconceived alternatives is at least mitigated. This allows us to articulate a new form of prospective realism for the biological sciences: one that allows us to tell prospectively, and not just retrospectively, which claims are likely to stand the test of time.

Novick, A. and R. Scholl. 2020. Presume It Not: True causes in the search for the basis of heredity. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 71(1): 59–86. [PhilSci Archive version]

Causal Reasoning in Biology 🔝

Once we recognize the central role of causal reasoning strategies in the epistemology of the life sciences, we can elucidate a range of further issues in the philosophy of science. The examples below engage in depth with modeling practices, hypothesis generation, scientific diagrams, the question of interdisciplinary integration (in the context of evolutionary developmental biology), and molecular network analyses.

Modeling Causal Structures: Volterra’s struggle and Darwin’s success (with Tim Räz)

This paper revisits the Lotka-Volterra model of predator-prey dynamics, taking into account previously neglected historical sources. In the methodological reflections that preface a key French-language publication on the model by Vito Volterra and his collaborator (and son-in-law) Umberto d’Ancona, we find a revealing hypothetical: To study predator-prey dynamics, we would ideally intervene on individual variables (such as prey abundance or predator voracity) in order to determine how those variables affect the dynamics of the system. Since such interventions are often infeasible, mathematical modeling is proposed as a substitute strategy. (While we do not frame the issue in this way in the paper, one can understand this as a commitment to the vera causa norm in a scenario in which the usual epistemic strategies for isolating and intervening on suspected causes are unavailable.) But how can one argue for the success of this substitute strategy in capturing the causal processes of the target system? We show that Volterra and d’Ancona were never able to show much more than that their model was capable of saving the phenomena, leaving it open whether the model really captured the interactions underlying predator-prey dynamics. Later researchers tried to test the model more thoroughly by developing model systems in the laboratory (involving single-celled species feeding upon each other) in which it was possible to intervene in a targeted way on individual parameters and so to establish the representational adequacy of the predator-prey model. But making a system susceptible of intervention is not the only way to study whether a model’s proposed causal processes match those operating in the target system. We show that Charles Darwin, in his equally model-based explanation of the origin and distribution of coral atolls, was able to get far in establishing representational adequacy by comparing the input-output-profile of the model and the target system, as well as by comparing the intermediate stages predicted by the model to those observed in the target system.

Scholl, R. and T. Räz. 2013. Modeling Causal Structures: Volterra’s struggle and Darwin’s success. European Journal for Philosophy of Science 3(1): 115–132. [PhilSci Archive version.]

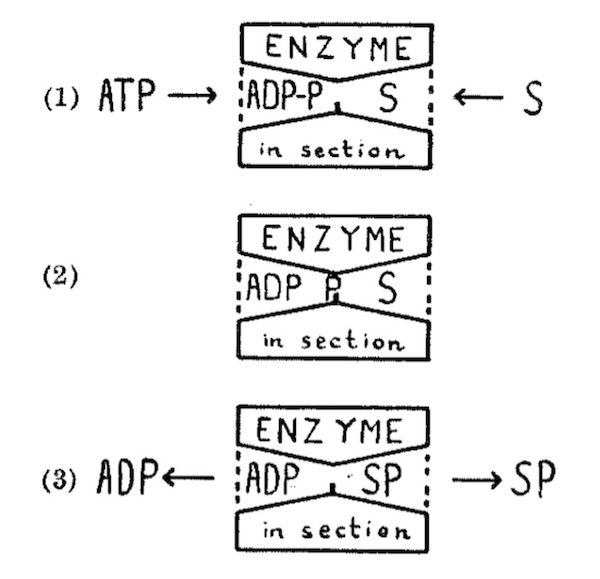

Discovery of Causal Mechanisms: Oxidative Phosphorylation and the Calvin-Benson-cycle (with Kärin Nickelsen)

Peter Mitchell’s Nobel-Prize-winning theory of oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) has been described as one of the most counterintuitive findings in science since Einstein and Newton. Philosophers and historians have looked as far as Heraclitus to explain how Mitchell could come up with the idea that ATP synthesis in mitochondria harnesses the flow of protons across the mitochondrial membrane (much as a turbine harnesses a water pressure gradient, although Mitchell would have rejected the turbine-analogy). Great surprise has been expressed at the fact that the solution to the problem was found by an outsider like Mitchell, who was not even part of the community of researchers who were investigating OxPhos.

In this paper, we show that Mitchell’s insight can be explained sufficiently by reference to the local research context. The search space for theories of oxidative phosphorylation was much more narrowly constrained than has been appreciated, and this permitted a systematic search. Mitchell was in a favorable position to explore a specific part of this search space, since his previous research on membrane transport provided the sort of mechanism schema that was required for the purpose. We suggest that this situation — defining circumscribed search spaces, and exploring them by trying mechanism schemata, often imported from elsewhere — is typical of scientific discovery, even in highly original, counterintuitive cases like this one. We show that similar ideas are applicable to the discovery of the Calvin-Benson cycle.

Scholl, R. and K. Nickelsen. 2015. Discovery of Causal Mechanisms: Oxidative phosphorylation and the Calvin-Benson cycle. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 37(2): 180–209. [PhilSci Archive version.]

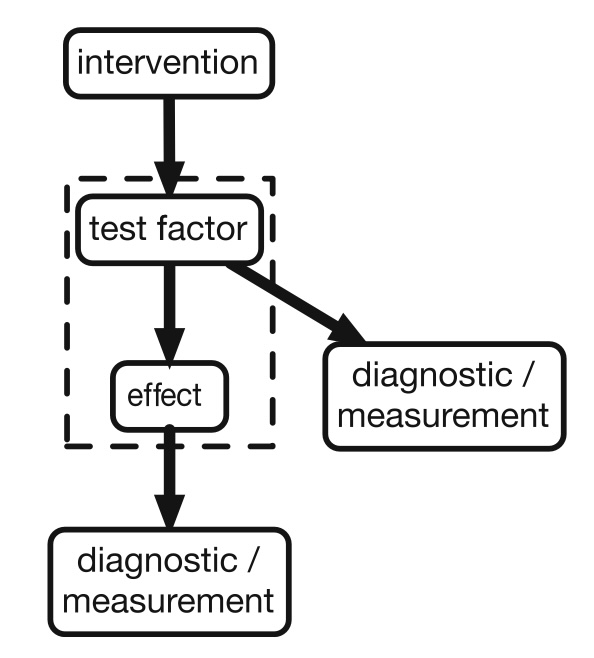

Spot the Difference: Causal Contrasts in Scientific Diagrams

Visual representations are high on the list of things that are lost in translation between scientific practice and the philosophy of science. Philosophy is almost exclusively focused on text, while the sciences are full of diagrammatic representations. This is especially conspicuous in the life sciences since the middle of 20th century. In this paper, I look at one of the key functions of these abundant diagrams: to visualize what I call “causal contrasts”, that is, to tell us what the outcome of real or imagined difference-making experiments is or would be. Such diagrams are often intellectually key in that they contain a research paper’s core findings — its claim to being an original research contribution. But what is more, causal contrast diagrams often involve images of physical artefacts that are part of the process by which difference-making experiments are realized. I invite readers to go to nature.com right now, to call up a paper from the molecular life sciences, and to be astounded by the ubiquitous images that fit this description. Take the images produced by fluorescence microscopy, in which specific experimental interventions are related to differences in the abundance and distribution of various macromolecules. Or take the countless gels on which macromolecules are physically separated and visualized, again in order to show how differences in their expression or quantity are related to differences in antecedent experimental interventions. Such diagrams are about as close to the bare bones of the epistemology of science as anything can be.

Scholl, R. 2016. Spot the Difference: Causal contrasts in scientific diagrams. Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 60: 77–87. [PhilSci Archive version.]

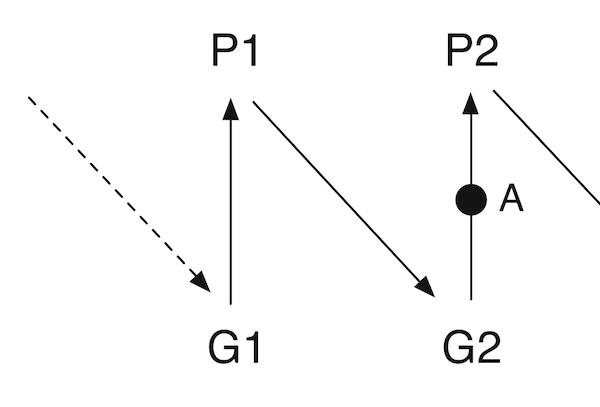

The proximate-ultimate distinction and evolutionary developmental biology: Causal irrelevance vs. explanatory abstraction (with Massimo Pigliucci)

We discuss the role of Ernst Mayr’s proximate-ultimate distinction in debates about evolutionary developmental biology (or evo-devo). In a classic 1961 paper, Mayr distinguished between two different types of questions that biologists investigate. Why did the warbler at Mayr’s summer home in New Hampshire start his southward migration on the night of the 25th of August? One kind of answer names proximate causes of the event. It describes the biological mechanisms that explain how a change in photoperiodicity and a drop in temperature cause the bird to migrate. Another kind of answer names ultimate causes. It describes the evolutionary history that explains why the warbler’s ancestors were selected to migrate southward when the days grow shorter and temperatures begin to drop. In subsequent decades, Mayr began to deploy the proximate-ultimate distinction against the emerging discipline of evo-devo, arguing that developmental causes are proximate and so cannot be relevant to explanations in terms of evolutionary causes. He and other evolutionary biologists identified an asymmetry: While ultimate or evolutionary causes explained the origin of proximate mechanisms, proximate mechanisms were taken to be largely irrelevant to the operation of ultimate causes. In one favored phrasing, proximate mechanisms simply “decoded” the genomic information within each generation, but they did not affect selection on genomic information between generations.

Since the emergence of evo-devo as a research field, a number of authors have attempted to explain how Mayr’s argument went wrong and why the proximate-ultimate distinction should be abandoned. We review two such attempts and conclude that they fail to diagnose the problems of the proximate-ultimate distinction adequately. Both critiques take the proximate–ultimate distinction to deny the existence of specific types of causal interactions in nature, but we argue that this is implausible. Instead, the distinction should be understood as a claim about which interactions to emphasize or de-emphasize in complete causal models of evolutionary change. On a pre-evo-devo view, developmental causes would have been understood as a mere background condition for the operation of natural selection. What has changed is not that developmental causes have suddenly been found to exist after all. Rather, it is that developmental causes are no longer seen as mere background conditions: They are often involved in setting the direction of evolution, and so must be foregrounded in our explanations.

Once the debate is reframed in this way, the proximate-ultimate distinction’s role in arguments against evo-devo can be seen to rely on an additional, implicit assumption. We call this the assumption of “isotropy”: that the variation produced by proximate developmental mechanisms is abundant, small, and undirected. If variation is isotropic, then only selection determines which genomic variants survive. If variation is itself biased, however, then the resulting organisms are determined both by the structure of the variation and by the prevailing selection pressures. It is thus the isotropy assumption that challenged evo-devo, not the proximate-ultimate distinction itself. We show that a “lean version” of the proximate–ultimate distinction can be maintained even when this isotropy assumption does not hold.

We connect these considerations to biological practice. According to one view, the investigation of developmental causes in evolution requires an analysis by optimality modeling: We determine what shape and function would be optimal if only selection were acting, and deviations from optimality are candidates for explanation by developmental “constraints”. We show that routine scientifice practice proceeds differently. From the beginning, developmental evolutionists have relied on experiments to show that particular developmental conditions are sufficient to cause the expression of particular forms, and that, therefore, no explanation in terms of natural selection shaping that form needs to be sought. If we find a trend towards additional toes on the hindlegs of a dog breed, this may be due to selection favoring variation for additional toes. But it may also be a consequence of generally increased body size, which leads to a larger limb bud during development, which leads to subdivision into more toes. And this, of course, is susceptible of experimental demonstration. Thus, the approach is less to demonstrate the insufficiency of natural selection to shape aspects of extant forms than to demonstrate the sufficiency of developmental causes to do so.

Scholl, R. and M. Pigliucci. 2015. The Proximate-Ultimate Distinction and Evolutionary Developmental Biology: Causal irrelevance vs. explanatory abstraction. Biology & Philosophy 30(5): 653–670. [PhilSci Archive version.]

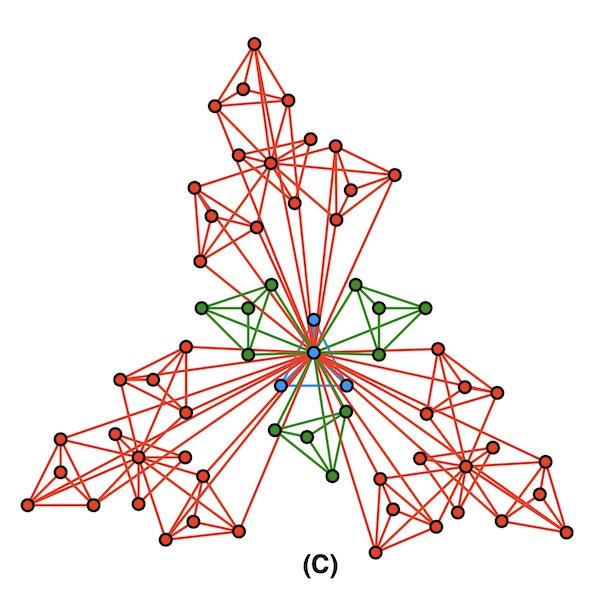

Network Analyses in Systems Biology: New strategies for dealing with biological complexity (with Sara Green, Maria Șerban, Nicholaos Jones, Ingo Brigandt, and William Bechtel)

This paper studies the new epistemic strategies that are enabled by network analyses in biology. My section focuses on network analyses as a heuristic for discovering potentially important causes, which can then be tested using more conventional interventionist strategies.

Green, S., M. Șerban, R. Scholl, N. Jones, I. Brigandt, and W. Bechtel. 2018. Network Analyses in Systems Biology: New strategies for dealing with biological complexity. Synthese 195(4): 1751–1777. [PhilSci Archive version.]

The Methodology of Integrated History and Philosophy of Science 🔝

Much of my philosophical work rests on a careful examination of episodes from the history of science (including the recent history of science). Because of this, one of my central methodological concerns is the methodology of integrated history and philosophy of science. What motives such an integrated approach? What are the best practices for relating philosophical theses to historical episodes? How can we justify normative philosophical claims on the basis of descriptive historical facts?

The Philosophy of Historical Case Studies

(edited with Tilman Sauer)

The title of our collected volume, “the philosophy of historical case studies”, is intended to have a double meaning: we are interested in a systematic account of how to use historical case studies for philosphical purposes, but we are also interested in the philosophical insight that we generate from historical case studies. The volume collects contributions that serve one or both of these purposes. The first part considers the history-philosophy relationship from a conceptual point of view. The second part revisits salient controversies in which different interpretations of historical episodes played an important part, such as the debate between Allan Frankling and Harry Collins about gravity wave research. And the third part looks at integrated HPS in practice, demonstrating by example the power of the approach to produce insight.

Sauer, T. and R. Scholl (eds.). 2016. The Philosophy of Historical Case Studies. Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science. Springer.

Towards a methodology for integrated history and philosophy of science (with Tim Räz)

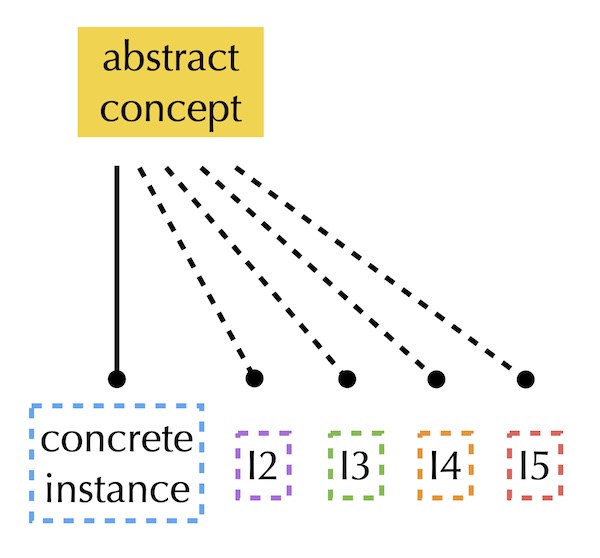

This contribution to The Philosophy of Historical Case Studies has three parts. First, we consider the basic motivation for pursuing integrated history and philosophy of science — instead of simply pursuing history of science or philosophy of science. Second, we present a partial typology of historical case studies. We find that discussions about the power and conclusiveness of case studies neglect the fact that case studies can serve a range of different purposes, and whether they are successful depends on whether they are suitable for a particular purpose. Third, we discuss the dynamics of the test of philosophical theses against historical episodes. Too often, it is implicitly assumed that the confrontation of philosophical theses and historical episodes is a one-off affair. We suggest a process of piecemeal adjustment that avoids two fallacies that we call the universal fallacy (“one case, two cases, three cases, therefore, all cases”) and the existential fallacy (“one counterexample, therefore, reject the thesis”).

Scholl, R. and T. Räz. 2016. Towards a Methodology for Integrated History and Philosophy of Science. In T. Sauer and R. Scholl (eds.), The Philosophy of Historical Case Studies. Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science. [PhilSci Archive version.]

Historical case studies: The “model organisms” of philosophy of science (with Samuel Schindler)

In integrated history and philosophy of science, we often look at historical episodes not just for their intrinsic interest, but also to say something about science more generally. We often claim that a particular episode exemplifies points that are more broadly applicable and give more general insight. However, this aspect of the practice of HPS has long been controversial. On what grounds do we take particular episodes — or even a handful of episodes — to be relevant to further episodes? Here we articulate one novel answer to this question. We think that case studies in the philosophy of science function in relevant respects like model organisms in biology. When we extrapolate findings from model organisms, it is usually on the basis of their relatedness to other organisms: The mitochondria of cows are similar to the mitochondria of humans because they have not changed too much since the last common ancestor of the two species. We argue that there are similar “relationships of descent” in the sciences. Scientists do not, as a rule, invent their methods out of thin air. Scientific practices — from experimental methods to styles of reasoning — are generally acquired by learning and imitation. This creates a natural basis for extrapolating results (carefully, of course) between cases.

Schindler, S. and R. Scholl. 2022. Historical Case Studies: the “model organisms” of philosophy of science. Erkenntnis 87: 933–952.

Scenes from a Marriage: On the confrontation model of history and philosophy of science

The view that the philosophy of science can be understood by analogy to the empirical sciences has gone out of fashion. It seems problematic to many to say that philosophers of science test their philosophical models against facts from the history of science, just as natural scientists test their models against empirical data. There are many reasons for skepticism that I discuss in the paper. A key one, however, is the long-standing criticism that historical episodes cannot genuinely test philosophical proposals, since we will always be in danger of unwarranted extrapolation (from one or several cases to many) or of cherry-picking our dataset (by testing our philosophical proposals only against favorable cases). Here I argue that these criticisms tend to presuppose an outdated model of empirical tests (enumerative induction and the hypothetico-deductive model), and that the difficulties disappear if we understand empirical inquiry more realistically. To formulate a more realistic picture of empirical inquiry, I rely on some of Hasok Chang’s work on the history-philosophy relationship, as well as on recent work on empirical inquiry by the so-called new mechanists. I suggest that the usual critiques of the “science of science” model are not compelling, while the model continues to promise many benefits. Chief among them is that it justifies how the philosophy of science can be understood as a normative project, even if we abandon the ambition of providing some kind of autonomous philosophical warrant for the methods of science.

Scholl, R. 2018. Scenes from a Marriage: On the confrontation model of history and philosophy of science. The Journal of the Philosophy of History 12(2): 212–238. [PhilSci Archive version.]

The History of Philosophy of Science 🔝

Unwarranted Assumptions: Claude Bernard and the growth of the vera causa standard

The physiologist Claude Bernard was an important nineteenth-century methodologist of the life sciences. Here I place his thought in the context of the history of the vera causa standard, arguably the dominant epistemology of science in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Its proponents held that in order for a cause to be legitimately invoked in a scientific explanation, it must be shown by direct evidence to exist and to be competent to produce the effects ascribed to it. Historians of scientific method have argued that in the course of the nineteenth century the vera causa standard was superseded by a more powerful consequentialist epistemology, which also admitted indirect evidence for the existence and competence of causes. The prime example of this is the luminiferous ether, which was widely accepted, in the absence of direct evidence, because it entailed verified observational consequences and, in particular, successful novel predictions. According to the received view, the vera causa standard’s demand for direct evidence of existence and competence came to be seen as an impracticable and needless restriction on the scope of legitimate inquiry into the fine structure of nature. The Mill-Whewell debate has been taken to exemplify this shift in scientific epistemology, with Whewell’s consequentialism prevailing over Mill’s defense of the older standard. However, Bernard’s reflections on biological practice challenge the received view. His methodology marked a significant extension of the vera causa standard that made it both powerful and practicable. In particular, Bernard emphasized the importance of detection procedures in establishing the existence of unobservable entities. Moreover, his sophisticated notion of controlled experimentation permitted inferences about competence even in complex biological systems. In the life sciences, the vera causa standard began to flourish precisely around the time of its alleged abandonment.

Scholl, R. 2020. Unwarranted Assumptions: Claude Bernard and the growth of the vera causa standard. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 82: 120-130. [PhilSci Archive version]

Miscellaneous 🔝

Confessions of a Complexity Skeptic

I wrote this piece in my role as commentator at a conference. It considers whether we need concepts from “complexity science” to understand two specific cases from macroeconomics. I answer no, since the relevant science seems more concerned with finding appropriate aggregate-level variables to describe the system’s behavior than with taking account of individual-level complexity. This prompts a methodological discussion of the proper use of historical cases in philosophical analyses.

Scholl, R. Confessions of a Complexity Skeptic. 2014. In M. C. Galavotti, D. Dieks, W. J. Gonzalez, S. Hartmann, T. Uebel, M. Weber (eds.), New Directions in the Philosophy of Science. Springer, pp. 221–234. [PhilSci Archive version.]

How we learned that Helicobacter pylori causes peptic ulcer disease

This is an invited German-language contribution on the discovery that the bacterium H. pylori is the leading cause of gastric ulcers in humans, which won a Nobel Prize for Barry Marshall and Robin Warren. The focus is in particular on how several strands of inquiry from basic and clinical medical science were integrated into a coherent overall picture. The article’s primary goal is to introduce a largely medical audience to some basic ideas from the history and philosophy of science.

Scholl, R. 2015. Peptische Ulzera und Helicobacter pylori: Wie wir wissen, was wir wissen. Therapeutische Umschau 72(7): 475–480.

Biomedical Research 🔝

Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Position and functional importance of the branch site preceding SMN exon 7 (with Julien Marquis, Kathrin Meyer, and Daniel Schümperli)

My very first publication was in the journal RNA Biology. We were studying a genetic disease known as spinal muscular atrophy, which is a leading hereditary cause of infant death. The disease is due to the absence of a gene called SMN1, which is required for the normal development of motor neurons. Although the relevant gene exists in two copies in the human genome, SMN2 cannot compensate for the absence of SMN1 because its seventh exon is omitted during RNA splicing. We studied some of the regulatory elements that affect whether the seventh exon is included or excluded during splicing, and assessed the potential of these regulatory elements as targets for gene therapy.

Scholl, R., J. Marquis, K. Meyer, and D. Schümperli. 2007. Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Position and functional importance of the branch site preceding SMN exon 7. RNA Biology 4(1): 34–37.